Why Silicon Valley Can’t Tell Its Own Stories

The stories are here. The industry to tell them isn’t.

At the start of this year (February), I decided to get serious about my interest in film. I’ve always been interested in cameras and media, but coming from a lifelong background in engineering, I never really saw it as a viable career path.

Story Company launched in early February, and a media frenzy ensued. Every startup and venture capital firm began to question their media strategy on X & LinkedIn (if it even existed). Video content began to flood the X timeline.

In April, Cluely released their viral launch video, earning 13M+ impressions on X. The frenzy furthered. The X timeline began to fill with poorly lit venture capital podcasts, 1m10s clips, emotionally distant talking-head announcements, and even more launch videos.

The production swell continued until roughly August, by which time launch video quality had significantly declined (and marketing budgets for experimentation dissipated).

At the start of 2025, I predicted a renaissance in film and the arts, but all San Francisco (the innovation center of the world) got was viral launch videos and podcasts.

Moving to San Francisco

I moved to San Francisco in September 2023. I was working on a voice-AI-enabled platform for software engineers to live-practice interviews with AI interviewers. It was the natural extension to the course company I was running at the time, called “Interview Pen” (a clone of my previous company, “Back To Back SWE” which I exited prematurely).

After arriving in SF, I unrolled my $99 foam mattress from Amazon in the corner of my co-founder’s studio apartment in the Marina. I was excited to stay lean and build the product out.

Little did I foresee, 2 guys living on the floor in a studio apartment together, one full-time on the product and another part-time, turned out to be a problem.

Aside from the expected squabbles about living situation, my co-founder had a very high revenue expectation for the company ($40,000/mo+) before he would consider going full-time. Or, he stipulated, we had to get into Y Combinator.

Eventually, I got kicked out. I ended up moving 2 more times that Fall and Winter within the city. Spending 1 month in SoMA, 1 month in Lower Haight.

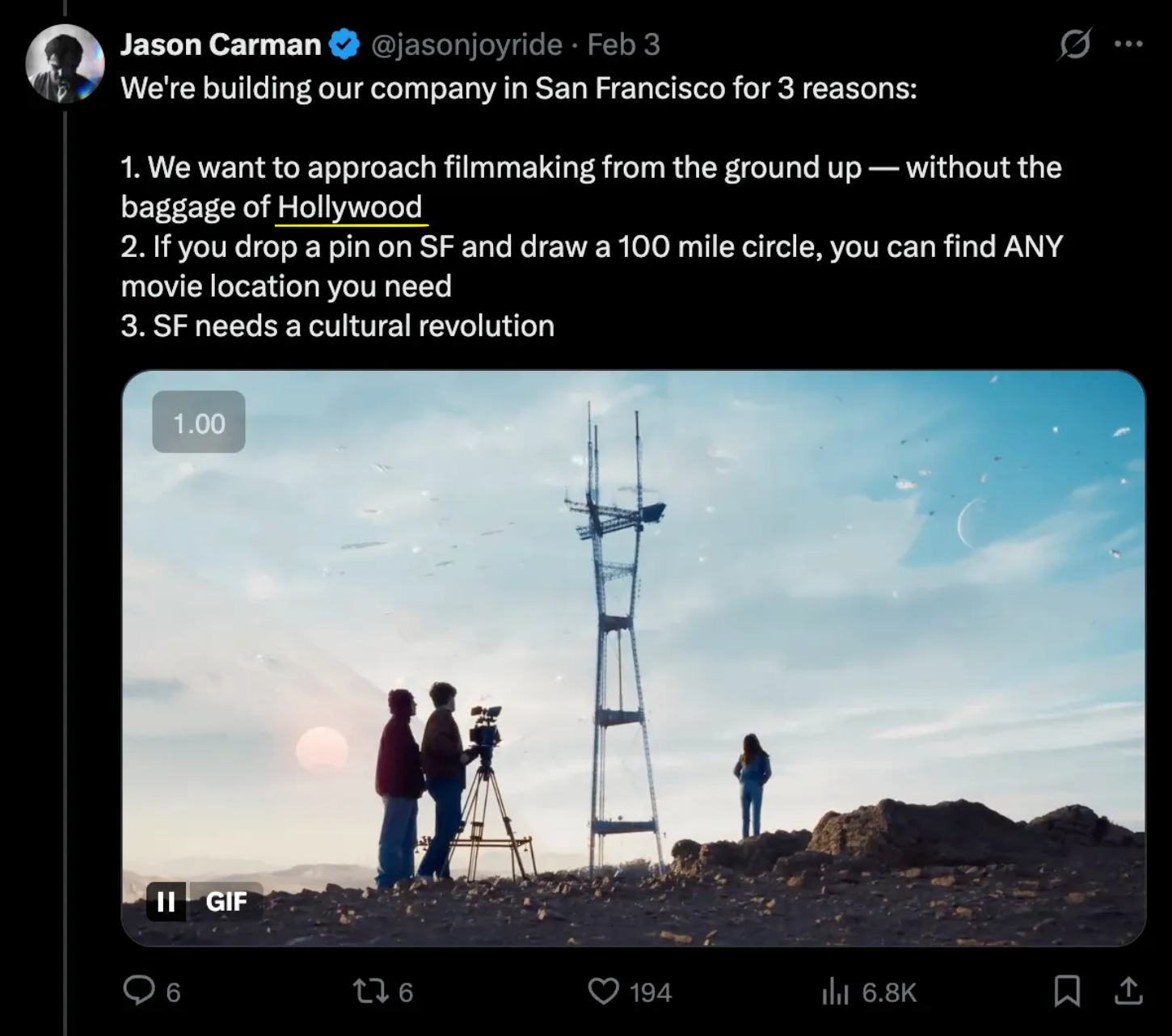

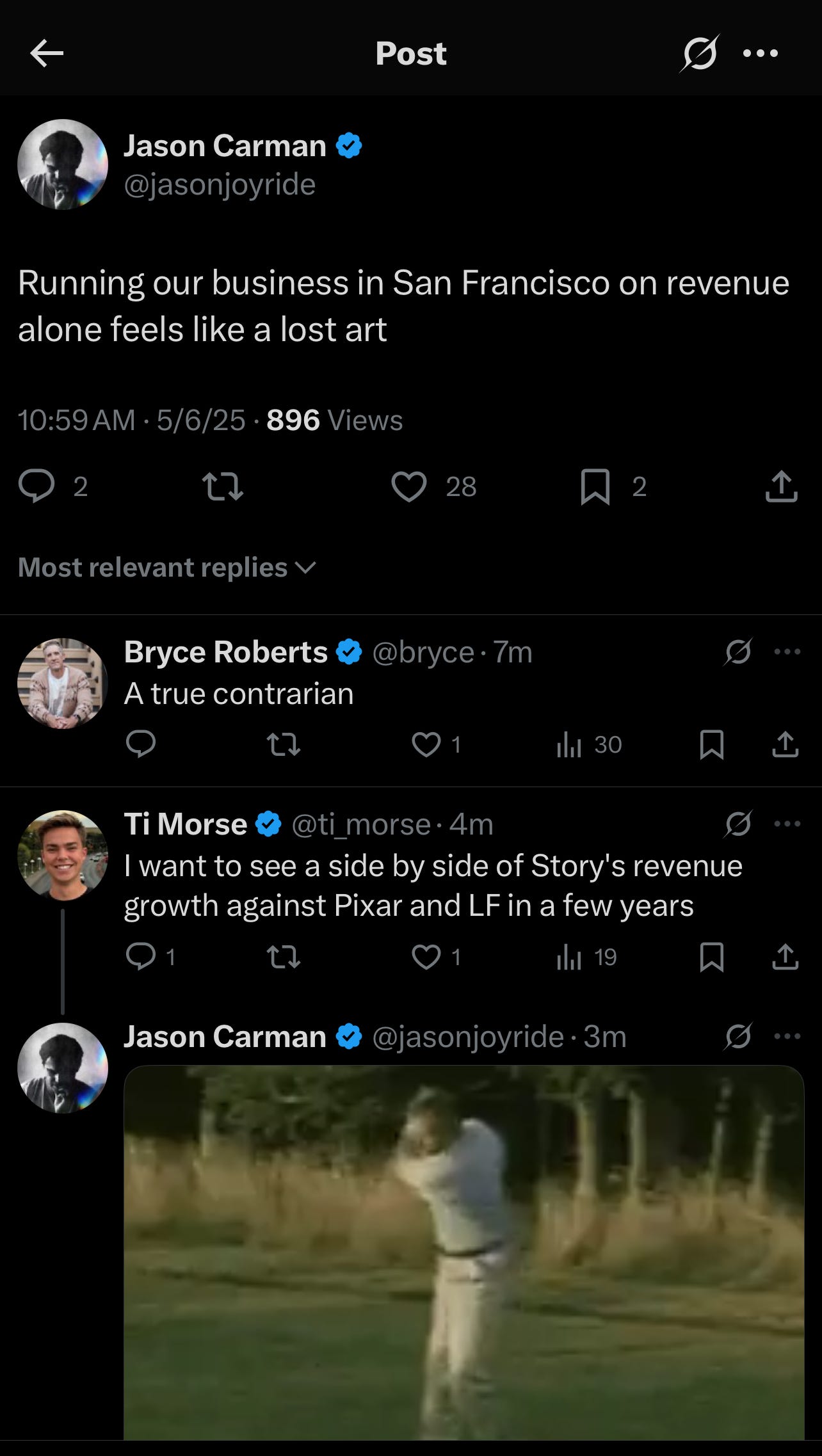

In the midst of this chaos, I started seeing some videos popping up on Twitter & YouTube from Jason Carman. At the time, video was only a hobby for me; throughout 2023, I was filming vertical shorts, trying to make them cinematic.

I reached out to Jason over DMs and actually ended up as a camera operator on this tweet.

Saturday Startup Stories

Jason Carman single-handedly carried visual storytelling in Silicon Valley from late ’23 to mid ’25, documenting the AI boom as it happened with his series “Saturday Startup Stories,” which featured a new deeptech startup every week.

I didn’t realize how insane a production cycle this was until I began attempting to produce work in February. To publish weekly, you have to be in all 3 production stages at once, at all times:

Development/Pre-production: Have a new story located or being researched.

Production: Filming the same day another episode is published.

Post-Production: Editing next week’s episode.

Maintaining the quality bar S3 had at this speed, while holding full-time work, is commendable (made more possible by Jason’s background as an editor).

The Cultural Core

Throughout this time period, all the way up to Story Company’s launch at the beginning of this year, no one was doing film in Silicon Valley in a big and serious way. It really was just 1 guy vs. the world.

Various YouTube influencers were touching here and there, but very few at the heart of innovation as it was happening, the cultural core of who was doing it and what this place is about.

Throughout 2024, I began to ask myself why this was the case. At the time, I was recovering from my co-founder leaving in January, faltered around in the Spring, before joining The San Francisco Compute Company as a Product Engineer in June.

So much was happening, but why were so few people filming it?

New Media

Jason’s work was the seed for more serious media operations to emerge in a culture that has historically denied image:

Print: Arena Magazine (Aug ’24)

In-House: A16Z New Media (Apr ’25)

Personality: Ashlee Vance/Core Memory (Jan ’25)

Podcast: Sourcery (Feb ’24)

“New Media” has always been a funny word to me because it’s just…regular media. We just didn’t publish our own narrative until ’24/’25. Most people in tech (including me) didn’t even know that narrative was deliberately created. It turns out there is a whole industry & city dedicated to only this.

Summer 2025

Between February and June, I was stumbling through documentary attempts and interviews, feeling and discovering my way through every aspect of filmmaking from first principles.

Why didn’t you like the video? The images are nice.. Story structure? Oh, what is that? Ah, screenwriting. Why does the image on that camera look washed out, and the other look crisp? Ah, cinematography? Logistics are a mess and I’m moving too slow. Ah, producing. The clip-on mic doesn’t sound as great as the overhead boom…where do I place it again? Ah, sound. I keep using music libraries and it doesn’t really fit the shape of the video. Ah, score composition. I keep visiting offices, moving plants around, but it never looks quite right. Ah, production design. One person coordinates all of these disciplines? Ah, directing.

Oh, there’s a whole school for this? Film school.

Lighthouse

In May, I began a documentary for Lighthouse (they help workers secure skilled immigration visas, like the O1). I had a general idea of what I wanted to do:

cut together multiple customer interviews

anchored by Minn’s personal narrative

with supplemental commentary from employees on their personal journey getting visas

But I didn’t really understand what I was doing. The overall message, structure, & direction of the work.

I conducted 6 interviews, where each interviewee thought they were giving a testimonial for Lighthouse. But walking in, I wanted to go deeper and explore a narrative of personal struggle, the real truth of the subject (which is just challenging and legally touchy to talk about, especially when in a position of power, talking to someone you just met, when you don’t know where the final video will go).

So the interviews captured watered-down replies, not really going anywhere, not really saying anything.

In the edit, I realized how clueless I was. Piecing together a narrative that I didn’t know, over poorly directed interviews that didn’t have the informational or emotional content I needed to make the video work (and I was doing everything myself: the producing, cinematography, sound, directing, editing — for free).

And after 8 production days and 1 ½ weeks of editing, the project was impossible to complete.

Film School

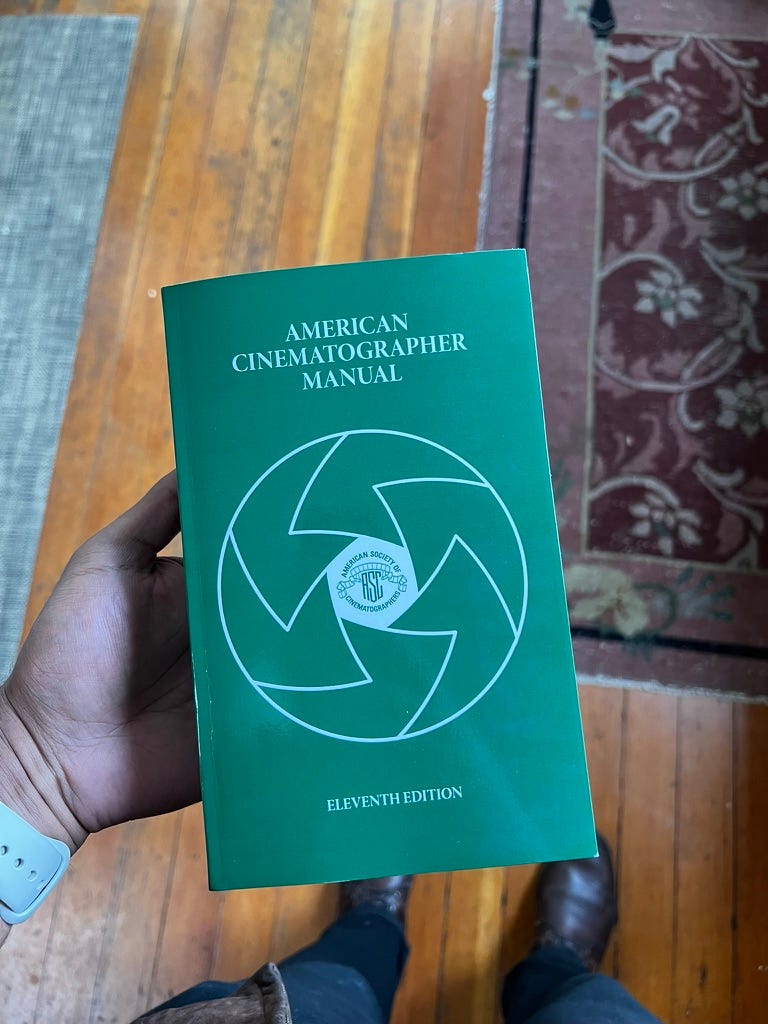

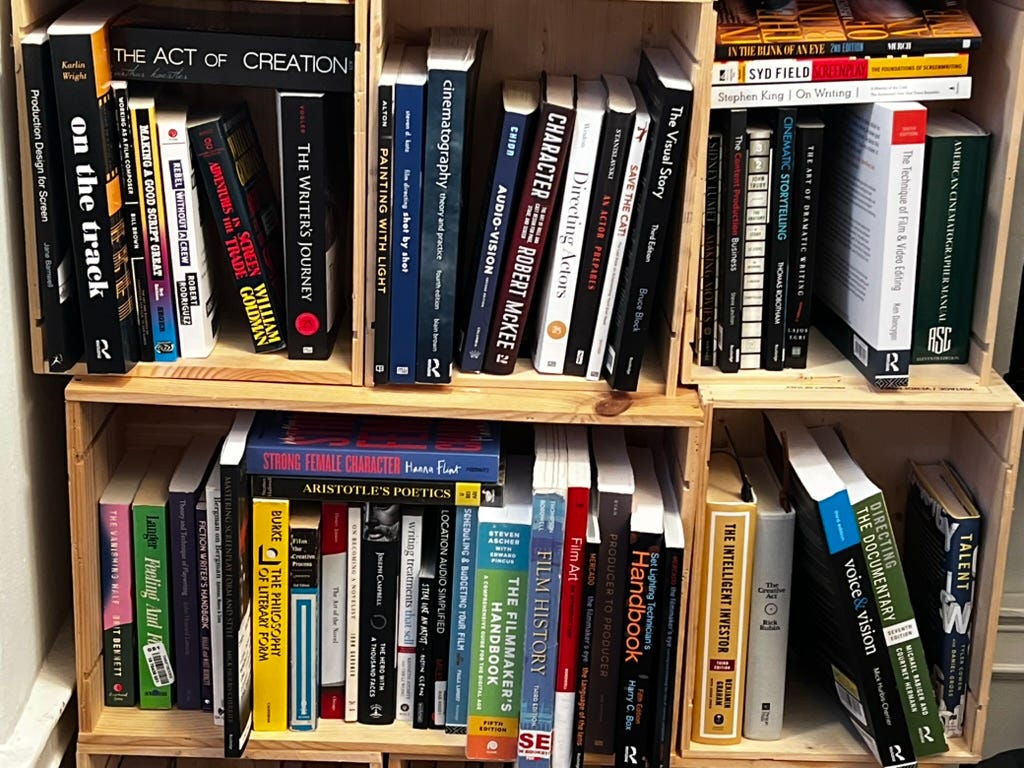

At this point (roughly in May), I realized I needed to actually know what I was doing. I resolved that I’d learn everything about every subject that touched the medium. So I started reading…

Cinematography, writing, directing, producing, production design, editing. I wanted to learn everything so my inability to “do the thing” would go away. After the Lighthouse shoot I read a whole textbook on directing.

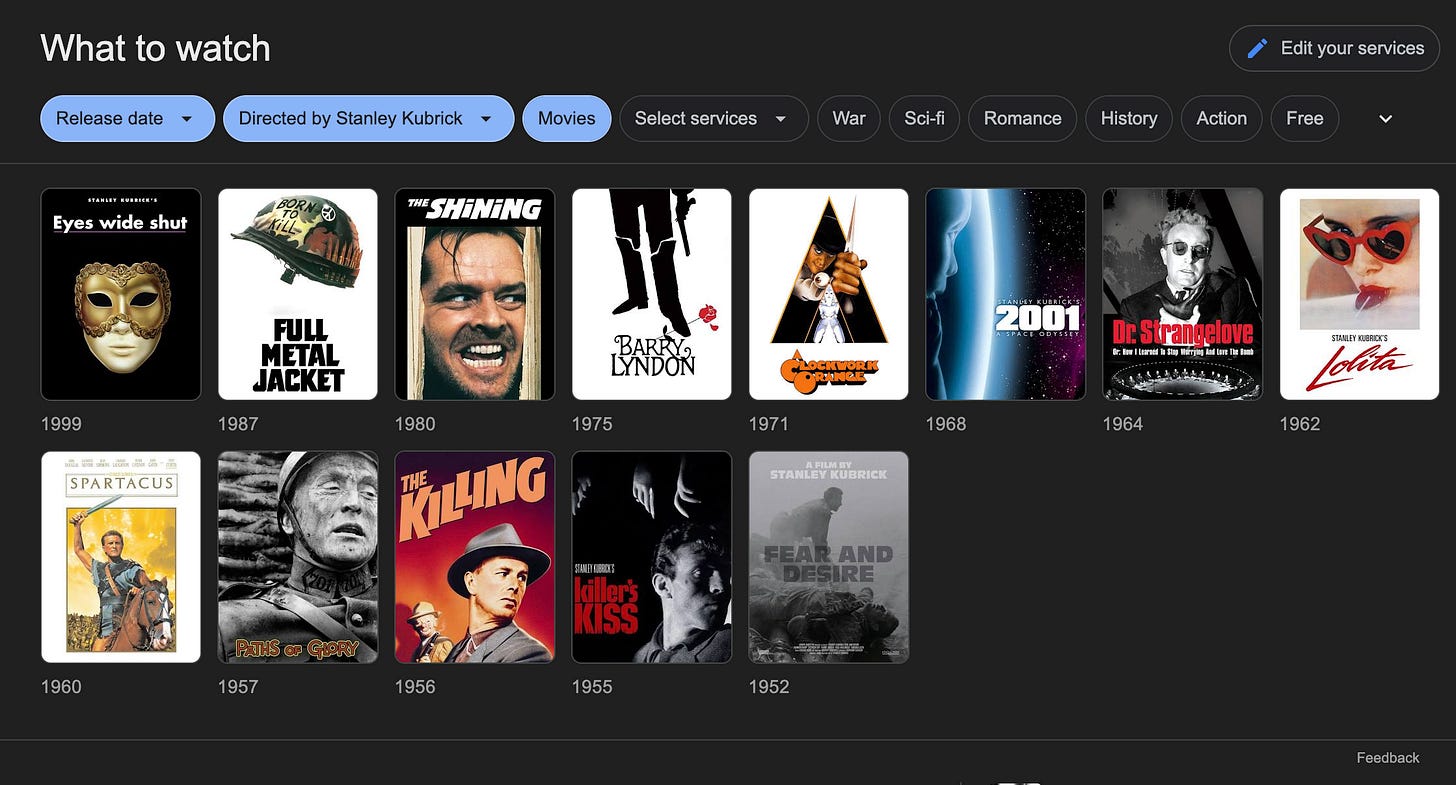

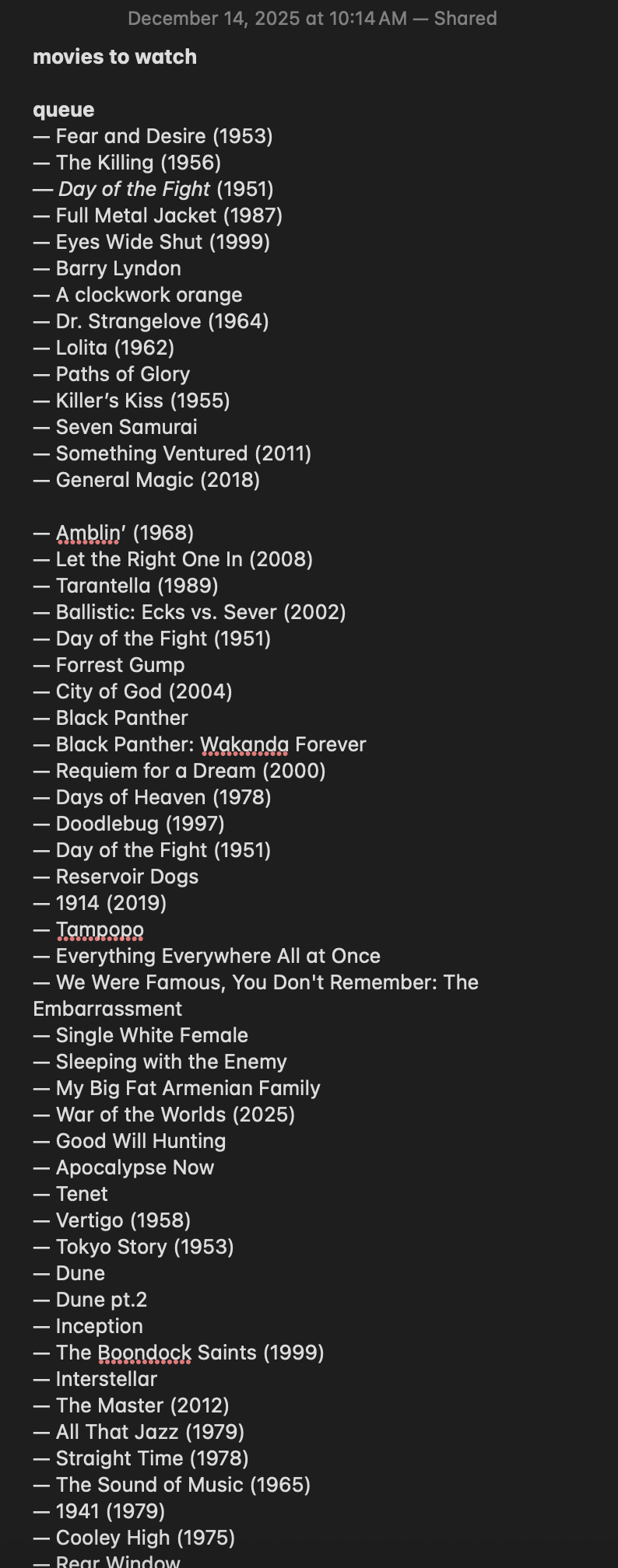

I began watching 4 films a week, covering almost 80+ films since late April. Internalizing story structure, shot grammar, cinematography principles, etc…

I didn’t realize it, but I was back in school again—this time as a first-year film student.

Offscript

Around May & June, I felt a vacuum start to form on the X timeline. Tech Twitter begins to circle certain keywords for 2-3 weeks spans, and the keyword at this time was “storytelling”. No one knew how to do it, or what it really meant. Narrative pressure was building.

One day I saw the post I was waiting for, from Juliana announcing Offscript, which went viral. Offscript’s team composition fits the perfect (only) shape that will work for commercial film production in Silicon Valley:

Juliana: Bridges the creative and technical world. As a former software engineer at Google + formal MFA in film. Can chop it up with people on tech Twitter. Can think both in impressions + reach + long-term signal, and artistic + aesthetic terms. Without both, everything falls apart.

Alli: Comes completely from the creative world. Providing creative direction and institutional production power.

Cam: Silicon Valley moves much faster than the normal production world. Productions need to turn around in days to a week to keep up with tech Twitter. Cameron comes from a rigorous post-production background.

It felt like a mathematician seeing a theorem they’d long suspected finally proven. That’s the only way it could have worked.

It was clear to me that Offscript could not have emerged from within SF, and it deepened my curiosity on why that was the case.

Barriers to a Storytelling Industry

The backstory above sets the context for what it looks like for a lifetime software engineer (with a recently acknowledged strong interest in film) to attempt this rare career switch.

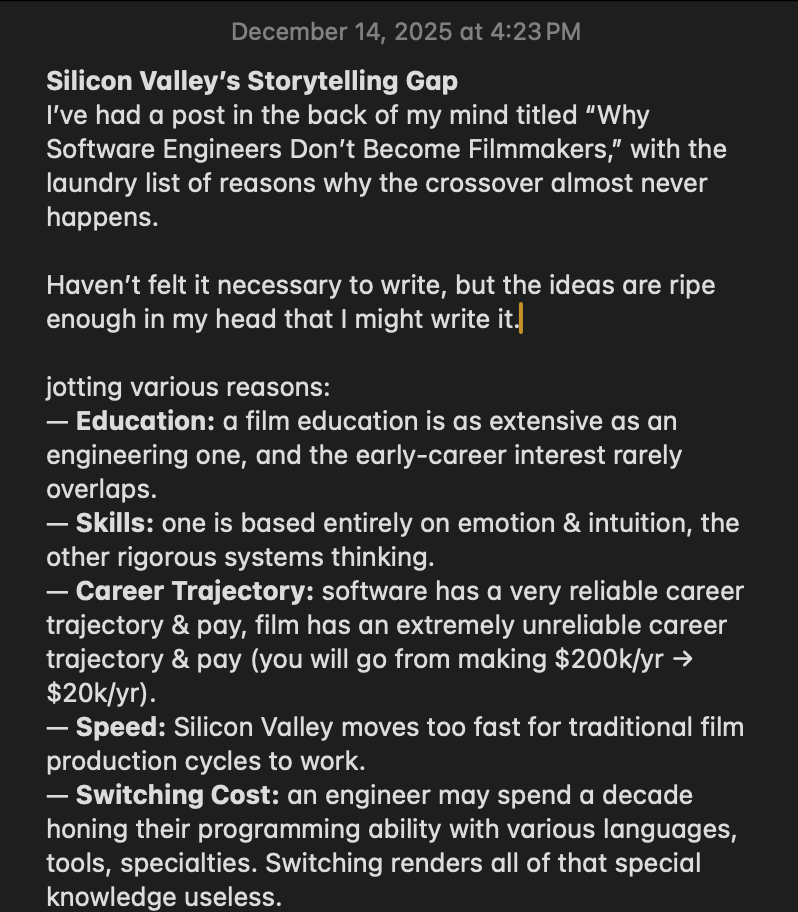

Since February, I’ve kept an Apple Note listing the challenges I’ve faced and how they might generalize to why Silicon Valley’s stories, the ones at the core, have been largely absent from the audio-visual medium.

These will read as a quick list with a conclusion at the end.

#1 — Education

A film education is as extensive as an engineering one. I went through 4 years of Computer Science at the University of Maryland. It involved extensive readings, practice, and hands-on projects.

A film education is no less rigorous. Film students go through a curriculum of 250-400 films over 4 years, getting hands-on experience collaborating with every department on full narrative sets, shooting student films, building countless relationships to specialties the craft requires.

Film as a medium is just as complex and demanding to have control over as the hardest programming assignment I ever did while in school. The complexity is just pushed to different problems (people, organizing ideas, logistical uncertainty, noticing what isn’t there in a performance that should be).

Those who study Film rarely pursue a dual major in Computer Science. Those who study Computer Science rarely pursue a dual major in Film. One is a field of the mind, the other, the heart.

#2 — Exposure

To progress in directing (& producing), you have to have mass exposure to every kind of audio-visual content. Feature films, documentaries, television, commercial spots, YouTube videos (Internet), etc.

This allows you to subconsciously absorb visual grammar (how a visual story converts to meaning, with what efficiency, pacing, rhythm, emotional texture), and build a mental library of preferences you can articulate in your own work.

People in tech (until culture has shifted in the past 1-2 years) don’t watch movies. They don’t watch TV. They’re building products heads-down, 9-9-6. There are many exceptions, but on average, your best backend engineer isn’t caught up with the latest show on HBO Max.

It’s only this year that I’ve started to study feature films, and I have a backlog of 500 films to study.

Studying feature films has been massively helpful for me to internalize visual storytelling. Showing, not telling. Writing with images.

Competence in the medium comes from exposure, which career engineers do not have.

#3 — Thinking vs. Feeling

Narrative film is about emotion delivery and creating change in the viewer. Software engineering is about critical thinking and system correctness + reliability. These are polar-opposite skillsets, attracting very different personality types to either profession.

Film favors the outgoing and personable, software favors the overly cerebral and pensive. Film is based on intuition and feeling; software is based on raw intellect and knowing.

Much of film work is based on not knowing, and instead finding. Almost every interview shoot I’ve walked out of where I “knew I got it” turned out to be an emotionally inert flop; those that I thought were a mess and unsalvageable often turn out to somehow work.

I’ve watched the movie Sinners 30+ times in theaters. Every time, before the show begins, I look around at the people behind and in front of me to collect an image of their emotional journey I can see as the film plays. I contemplate why we’re all there. Why do we pay $10-20 to sit in a dark room, staring at a large screen of moving images?

It is to experience emotional satisfaction. A beginning, middle, and end—that connects to a meaning.

Whether it be emotional catharsis, watching a horror movie, or finding true love, watching a romance. The product is invisible, existing only in viewers’ minds. Like a distributed database of emotional values. Your career as a director advances when you move as many of those distributed values in any desired direction.

On the other hand, startups are about creating tangible products. Those users can interact with and gain value from. Whether software UI or hardware, effort can go into seeing a tangible result.

The result of a film is intangible. You can never touch or see culture. You just feel its shape from your set of experiences with the world.

#4 — Talent Density

World-class technical talent moves to San Francisco to work at or build companies. World-class creative talent moves to LA or NYC to work at the highest level for their specific medium (in film, this is narrative features/commercial work/documentaries).

Any given film work, even a simple talking-head announcement, may touch 6+ creative specialties:

production

directing (observing and managing performance)

cinematographer (will handle both camera & lighting)

sound recordist

post-production

editor

colorist

graphics (design + motion)

The density of creative talent for any given discipline you’re hiring for will be a harder search here in San Francisco. Most creative talent physically isn’t here. The best are booked out 1 month. Some of the best cinematographers in the Bay might find themselves in the middle of the pack in strong talent markets like LA or NYC.

The best talent moves to where the best talent is. Where the opportunity to go as high as possible in your career is. And for creative people, that is (currently) not San Francisco.

This creates a vicious cycle. Without concentrated talent, standards stagnate. Without rising standards, there’s no visible career path. Without a career path, talent leaves—and the loop tightens.

Jenny Gao’s timely “50,000 Art Hoes Will Save San Francisco” talk playfully gave a nod to this serious labor shortage. (apparently the talk wasn’t filmed in San Francisco, rather, Sydney, Australia)

#5 — Collaboration

Film is a highly collaborative medium. It involves communication between many parties: subjects, clients, vendors, locations, crew, and your own creative staff. You have to talk to a lot of people. You must develop strong interpersonal skills.

Most people in tech (and San Francisco) are introverts. They can start beef on Twitter, but not go outside for 2 days. The city attracts those who were quiet or outcasts in some way early in life, and who are now on a revenge arc (which manifests as company-building).

A majority of software work can be completed individually (with more or less cross-functional collaboration required, depending on org and project size). An engineer can code up a backend endpoint, deploy, and it can stay operational for 4+ years—without talking to anyone.

Film work is a process of constant handoffs and clarifications. From project inception to completion, a never-ending alignment between stakeholders and creative staff. Being a clear communicator is a requirement.

This makes film talent less likely to emerge from those who naturally gravitate to San Francisco for a tech career.

#6 — Visibility

Film is a very visible medium. People bet on people, names they trust. Trust comes from the belief that someone can survive 10,000+ creative decisions and still get it right. So name & face become as much the product as the product itself.

Chain of Visibility: Actors are the most visible, since they are on-screen. Directors are visible as the creative authors of the work. Producers are visible for making the thing happen (except more in industry circles than general public awareness). Almost every other role: cinematographer, composer, etc. also maintain industry visibility.

Visibility is how you survive. It’s how producers get sent projects to produce. It’s how directors get projects to direct. It’s how composers get projects to compose. The industry runs on being seen—being easy to locate & say “yes” to.

Software engineers like to be invisible. They leave their GitHub avatars unset. They set their Twitter avatars to an abstract gradient. Say the most with the fewest words. Efficiency. Economy. In an ideal world, they want to make $500k+ TC with no one knowing their name. Why would you need to know my name?

Striving to be visible signals incompetence; the best produce the most while being completely invisible. Being invisible is high status.

This cultural attitude, this survival mechanism—having been ingrained across a lifetime, is almost impossible to unlearn.

#7 — Income

Software engineers make a lot of money. Over $200,000/yr for good roles, up to $500,000/yr+ into senior roles. Your first year as an independent director, you might be lucky to take home $20,000 (a 10x decrease)—after living expenses, investing in gear, building a portfolio of work, investing time learning, etc.

Throughout the year, I would help Sonith (from ZFellows) and 50y film their podcast + a mess of other freelance work. This allowed me to just get by and spend time studying and developing my own projects.

Arlan

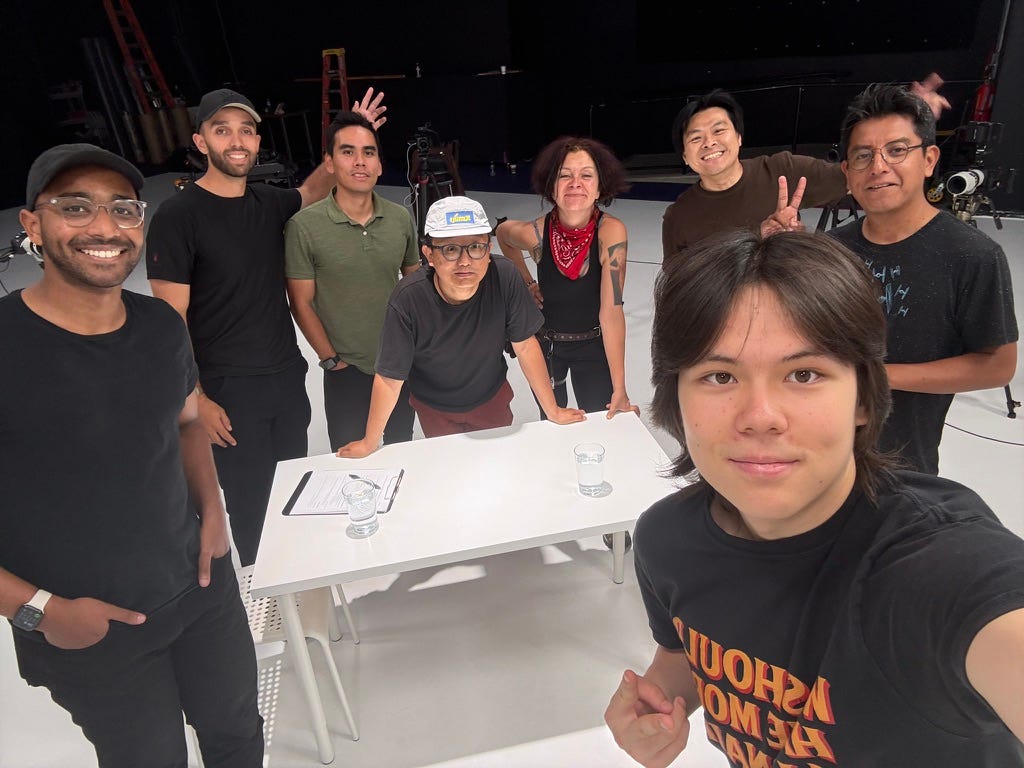

By late July, I realized I wasn’t being intentional about the projects I was taking on. So I decided to produce a proper interview with an actual set to show I was capable of working with a crew.

I had a concept for an infinite white room I’ve wanted to do for a while. I knew the project would take some investment so I waited for the right person to do it with. Eventually I stumbled across Arlan (from Nia) on my timeline. I DM’d him.

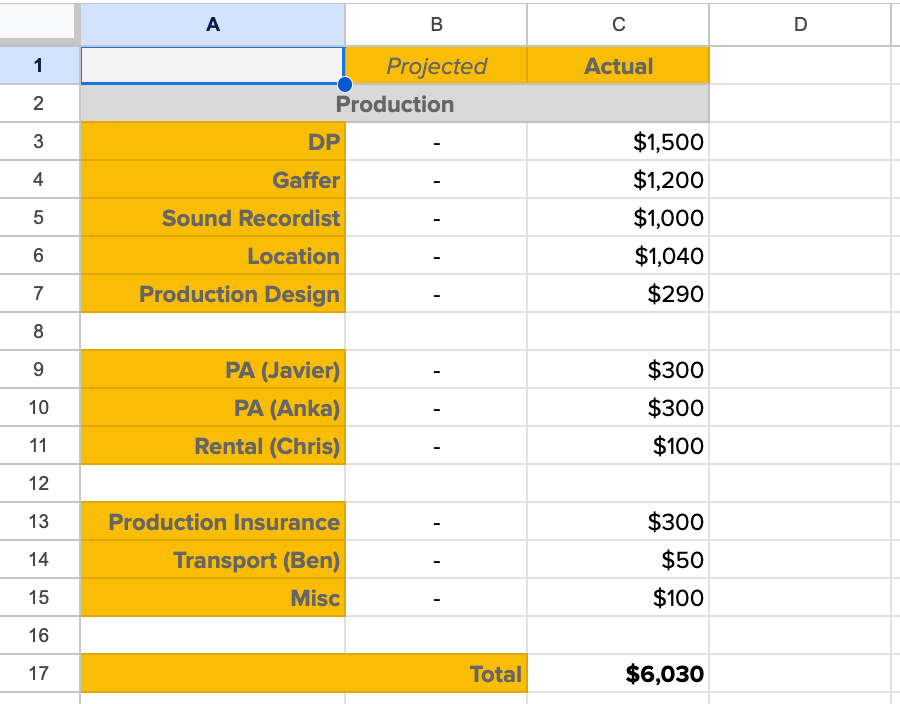

In August, I produced the project, assembling the crew and going way over budget.

It cost ~$6,000 to produce. Just a simple infinite white room concept. Film production is more expensive (and inefficient) than most people in tech realize.

The below is a breakdown:

Across the final full interview (61k+ impressions) + 4 clips (124k, 30k, 14k, 1k…) the content earned over 230k+ impressions. At $15 CPM (not sure on Twitter’s exact pricing), a ~$3,500 return in earned attention. So not that terrible. I wasn’t producing this for the reach, it was a portfolio item to show I could think cinematically & direct a crew.

Leaving a high-paying, predictable, stable career for a capital-intensive, emotionally intensive, unstable career you’re not even good at yet—doesn’t make much logical sense for anyone with a strong tech career.

It especially doesn’t make sense during one of the greatest wealth creation events in technology history (’22-’25).

I’m ending the year still barely getting by in income (mostly because I hadn’t decided to commit to the career until a month ago and kept turning down paying projects).

#8 — Switching Costs (Skill)

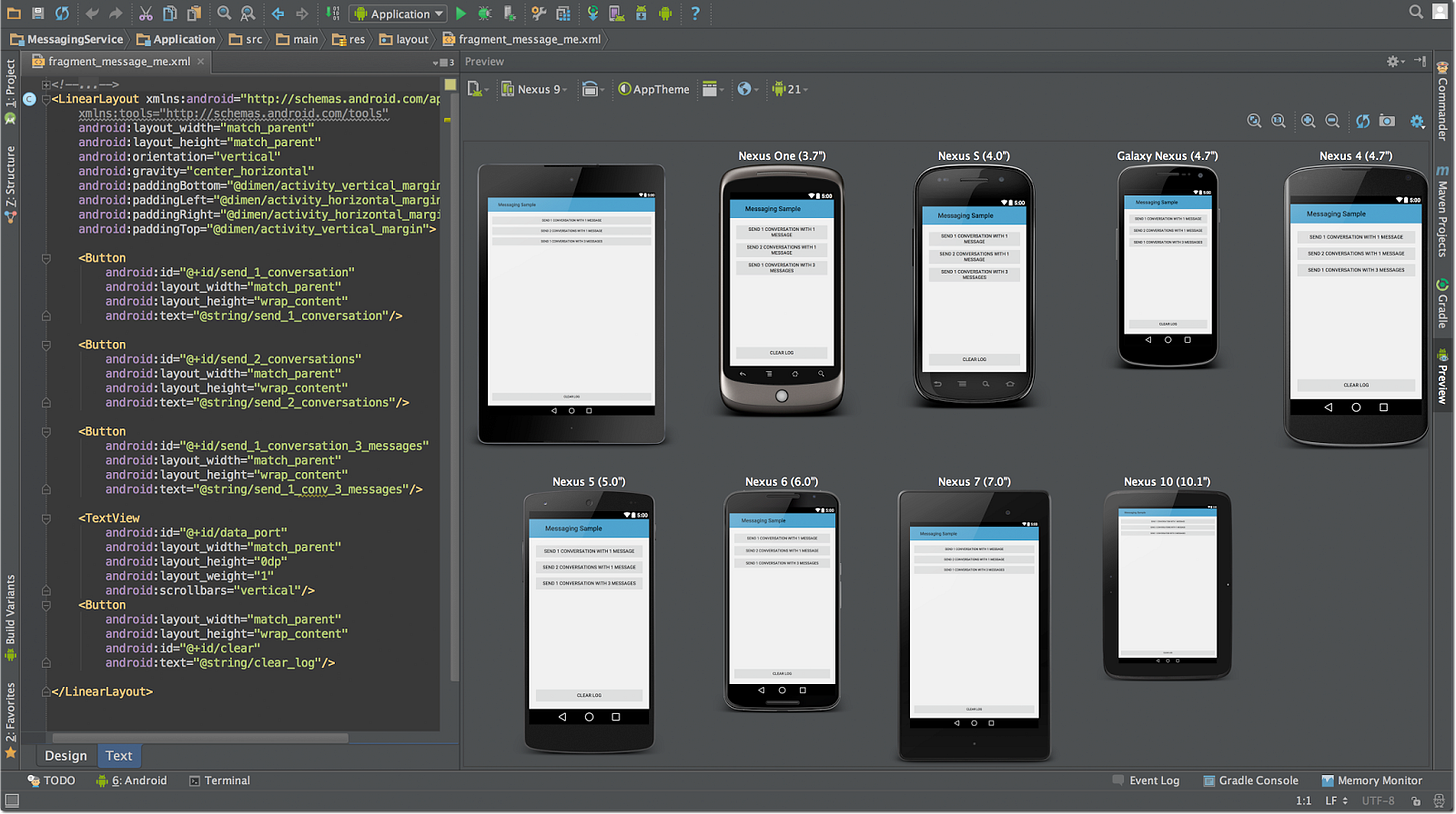

I started programming when I was 16. I wrote Android apps for my Samsung Galaxy Note 4. I remember the first time I ran Android Studio, and a blank screen with “Hello World” text in the center popped up. It was magic.

During high school, I would take lessons on Treehouse, learning JavaScript, C#, Java, frontend frameworks, backend—I wanted to know everything.

Most programmers spend years honing their taste in code and patterns through self-education, projects at work, and code review. An eye for good code takes at least 4+ years to develop. Frameworks and languages can take 6+ months to pick up and become professionally proficient in.

Switching to film, you throw all of that specialized knowledge away. None of it matters. It’s a completely different set of skillsets (most interpersonal), in a completely different medium, with completely different goals.

I’ve “thrown” a decade of specialized knowledge away in full-stack engineering. From 16 to 26. “Thrown away” a 4-year Computer Science degree that defined who I was.

It’s been a challenge for me to write screenplays in plain English after spending half a lifetime in VSCode/Cursor. I always feel the pull to open an IDE…so I can feel immediately “useful” again. To feel that sense of control from running a program, it not working, fixing it, then running again.

What’s helped me is realizing that in film, the same architectural rigor exists, except in a different way. Instead of software architecture & abstractions, you have story architecture & dramatic beats. The architecture is emotional and event-based rather than in code.

#9 — Learning Curve

Beyond a formal film education being very helpful, much of film work can only be learned through hands-on experience. Working with documentary subjects from behind the camera or narrative actors on a set. Trying—seeing what works and what doesn’t in the edit. What wasn’t there that we want? What was there? Over and over again.

Technology workers do not have this required experience. You have to do the thing to get it. But you won’t be doing the thing if your career is not in…the thing.

Since February, I’ve grappled to understand story structure. In March, I thought I had it, but I didn’t. In May, I thought I had it, but I didn’t. In November…

Only 9 months later, after extensive study and painful learning experiences, do I feel I have a strong, intuitive grasp of dramatic structure (at least at a 2nd-3rd year film school student level). I can look for it and see it in any narrative work. I can sense emotional texture—where it sits, where it should sit.

This intuitive nature to film takes a decade+ to develop a sense for at a subconscious level.

#10 — Identity

To switch from a technical career to a creative career, you have to undergo an ego death. You have to shift both your internal perception of who you are, as well as your external brand of who others believe you to be professionally. This can take years.

Technical peers look at creative pursuits with skepticism. There is a “waiting to see if they make it” dynamic always at play.

I’ve watched my previous network of technical peers stop texting me, stop reaching out for coffee chats. There is just not much of an overlap anymore to maintain constant communication. Our paths do not intersect to an extent where value exchange can go both ways.

What I’ve found is that the network just turns into creative people. Writers, editors, cinematographers, other directors. But that transition is a painful and lonely one.

This happens simultaneously to the period of time when you aren’t yet great at the thing (and financially struggling). To become great, you have to publish publicly while still an amateur. You have to embarrass yourself to progress.

A software engineer always has to be aware of the tools they have to solve a particular problem. New tools come out every month, you try them on the weekend, tinker, test, and tweet about it. It’s how you progress in your career, stay relevant, and survive.

I had to become OK with not being on that cutting-edge anymore. Not knowing the newest database or agent framework. This was especially difficult during ’23-’25 when so much was happening in software. I can still understand concepts—I’m just not embedded in the world day-to-day. It is impractical and impossible to do so as a filmmaker. You have 100 years of cinema to catch up on…

This is something I’m still not totally over.

#11 — Builder Culture

Until 23/’24, the culture of San Francisco was a “shut up and build” culture. If you were talking, if you were public with your image, you must not be building anything that important. Being visible and perceived as vain meant career death.

With AI making the building of many mid-tier consumer software products accessible, the challenge shifted to distribution. Getting people to know about the thing. Why the thing matters. Storytelling.

A whole industry realized a massive surface area of attention they were ignoring (X & LinkedIn). 1m10s podcast clips were getting 300k+ impressions on X (300 * $15 CPM → $4,500 in raw attention sitting on the table if you take 20 minutes to edit out a clip).

This happened in parallel to Jason Carman ripping a documentary a week. People in technology began to see the value in seeing your culture accurately represented in media. The value of scaling image.

Every cultural movement is a time that comes and passes. Sometimes it just isn’t the right time for a certain idea, or movement, or work of art. This was Silicon Valley pre-2023.

A cultural window is opening.

#12 — Industry Awareness

I’ve never been to LA. Until February of this year, I wasn’t even exactly sure what Hollywood did. I watched movies as a kid, but I never contemplated further to seeing myself having a career in film.

2 major industries, the entertainment and technology industry, the former valued at $2-3T, the latter $5-8T (thanks Claude), are almost completely unaware of how the other works.

And they aren’t really interested in figuring it out, either. For creative work, humans are at the heart of the work. For technical work, technology and systems are at the heart of the work. The best creatives are (usually) the least technical, the best technical talent is (usually) not the most creative.

Silicon Valley is insular in culture. Founders talk to each other in “group chats” (I’m apparently not in any of them..), 1 Twitter post can take over the narrative of a whole industry for the day, <100-1,000 accounts set the agenda for 500k-1M+ onlookers. We don’t watch the Super Bowl.

We’ve traditionally been culturally tone-deaf and closed off.

On the other hand, entertainment is all about culture. Its creation, transformation, death, rebirth.

#13 — Access

Filmmaking runs on access and trust. You can only tell stories with people whom you have access to, and who trust you enough to step in front of your camera.

When someone wants to do content work, they will ping their network and go with the closest, safest bet. Other engineers, founders, investors—who have an interest in media. But not filmmakers. Filmmakers are not in the network. Local agencies and freelancers can do the work, but they’re not technologists.

Because of this, some of the best visual artists in the world are unable to access Silicon Valley’s stories. It’s both a network and communication problem—visual artists aren’t in-network, and most don’t have the chops to go back-and-forth on both strategy and artistic concerns.

The best artists live in a world of feeling that isn’t grounded in pushing metrics or business results. You can’t put up a job listing for “storyteller” and expect the applicants to be good; you have to identify and mobilize visual arts talent behind a fresh narrative they own.

To tell Silicon Valley’s stories, you have to become an insider.

#14 — Running a Production Cycle

To create a culturally significant media operation, you need to create a production machine. This can look like (1) timeline takeover, posting multiple times a day: clips, longform, live (like TBPN), or (2) infrequent & value-dense, releasing 1 magazine a quarter (like Arena Magazine).

In either case, you must be consistent in the release cadence your medium requires of you (while maintaining tone and quality), and the production operation must be designed to run forever (while adapting to culture).

Prospective media operators in SF do not know how to run a rigorous and logistically intense production operation. This talent exists in LA and NYC.

This creates the grand irony of TBPN being based in LA instead of San Francisco.

#15 — Motivating Creative Talent

Motivating creative talent is different from motivating engineering talent. (The best) creatives care about:

constantly going deeper on their craft

doing culturally important work

seeing alignment between the director/founder and the story

feeling the director/founder understands the technicalities of their craft

fair pay, a respectable living

loving who they work with

surprising themselves (and others) with what they make

Engineers care about similar things, but creatives are much more focused on skill & process as output, over clean-cut salary, stock package, and bonus compensation. World-class creatives don’t really care about that; they’re obsessively craft-focused.

An engineer can not care about the company, make $500k TC, and go home feeling fulfilled. No matter how much you pay a creative, if they aren’t connected to the work, pushing the boundaries of their skills, pushing their understanding of their medium, great work won’t happen.

I always make it a point to study all of a creative’s work before meeting with them, so I can articulate back to them exactly what I find interesting or applicable to a project. If it’s a cinematographer, I’m watching every second of footage on their Instagram and website, looking for colors they like, themes, moods they gravitate to, etc.

#16 — Unemployment

Creative work is project-based. Very talented people can go weeks without work—not because they’re struggling, but because that’s simply how opportunities flow. Dry spells are built into the career.

In technology, unemployment puts you at zero status. You’re overlooked after introductions at parties, your friend group stays casually aware of it, companies become reluctant to hire the person someone else hasn’t hired. (unless, of course, you were just building your own startup all along…)

When you can attach your identity to a powerful company, you become someone in the ecosystem. You have leverage: relationships & information. You can get someone else a job, share hard-earned lessons from work on Twitter, angel invest in others with your income. You can give people something.

A creative between projects finds no social place in tech. They don’t have a “prev. OpenAI, Stripe, Uber” to connect in conversations. Their skills get overlooked, they can’t find many peers to lean on, and the housing gets too expensive.

So they leave.

Initiatives like “The Intersection of Art and Technology”, TIAT are safe 3rd places for creatives in tech. We need more of them.

#17 — Drama

Story comes from drama. Characters collide with reality and make critical choices that define who they are. The quality of a film is directly tied to how vulnerable, real, and open people can make themselves.

There are varying degrees of drama, from bickering with your roommate over food they stole from your side of the fridge—to a sprawling downtown shootout in LA involving dozens of cops, people falling left and right.

In either case, the drama is rooted in true events and not fabricated. Fabricated drama creates false meaning; it creates nothing.

“Drama is life with the dull bits cut out.” — Alfred Hitchcock

Many founders and investors are not ready for the level of vulnerability the best storytelling requires. Revealing struggle publicly makes you weak—a target. When in reality, vulnerability and relatability are core to the empathy mechanism that makes film work—letting others see themselves in you and your story.

So some of the best stories still stay hidden, and much emotional landscape has been totally unexplored.

#18 — Dreams

The dream people move to San Francisco with: build a high-growth startup that gets millions of users, earn respect among industry peers, and make a lot of money.

The dream people move to Hollywood with: direct, produce, star in a feature film that has widespread cultural influence and impact. Maybe get famous. Also make a lot of money.

Filmmakers want to make films. Founders want to build a product.

A film studio is not a startup. Startups grow fast. Film studios, unless they take on capital or quickly create original IP, do not. They are service businesses.

Top startup talent is not interested in creating a service business. They want to swing for the fences. Top creative talent is not interested in a high-growth venture; they want to produce the best art.

Two opposite motivations.

#19 — Platform Gap

The world’s greatest visual storytelling talent is on Instagram or YouTube. Sometimes, with a presence on X. Some aren’t even online in any capacity.

The technology industry is on X.

A composer friend who scored 2 of my (very early) documentaries—I met at San Francisco’s first 222.place event doesn’t have any social media except LinkedIn (which he doesn’t maintain).

Talent doesn’t even get to see the opportunities for storytelling here—because they just aren’t on X.

#20 — Cinema vs. Socials

The “laws of gravity” for attention in cinema vs. Instagram vs. Twitter are completely different. In cinema, you have your audience captive for 2h10m. You get them through the door with a compelling premise, but once they’re in their seat, they have 1 choice for what they can watch.

In a theater, you can spend time building long character arcs, write drawn-out dialogue exchanges, build suspense with score and silence. The watcher is glued to their chair; nothing is competing for their attention in a totally dark room.

Twitter and Instagram have completely different rules. We’ll focus on Twitter:

Default Muted: Videos are muted by default; you have to lean into visual storytelling in the first 4 seconds to get someone to stay & unmute. Clearly seeing the face of someone talking to you vs. abstract visuals will outperform.

Contrast: Quick cutting visuals, movement, & color contrast stand out on the timeline. Many Twitter users in tech watch in dark mode. Posting a white GIF or video in a bright white room increases the contrast of your video against other content competing for attention.

24s-1m30s Video Length: Drop-off on a Twitter video can be 60%+ of watchers after 20s. Clips under 1m30s with a story arc see the most engagement. Information-driven content can budget 30s-1m for maximum engagement. Anything longer and shareability drops off steeply. Viewers will need more context or pre-existing trust that the content is worth their time.

Emotion Above Everything: Making watchers feel something is all that matters. High production value is downstream of triggering a feeling of presence and immediacy. “This must be important.” Changing emotional charge every 10-15s. A video recorded on an iPhone can outperform a $100k+ commercial if its emotional architecture is stronger.

Many classically educated visual storytellers won’t have hands-on experience with platform idiosyncrasies.

The best tweets are immediate to comprehend. One morning I saw a podcast from Anthropic and decided to scribble a few slides breaking down the cinematography. It took me maybe 20 minutes. The post went (semi-)viral. It was well-timed, 1 sentence, 4 skimmable photos, and information-dense. You could comprehend the message in <10s. 221k impressions * $15 CPM = ~$3,300 in earned attention, just from 1 sentence and 4 scribbled slides.

You can spend 2 weeks, and thousands of dollars, making a documentary and it could only hit 5k in reach on Twitter. Socials don’t reward cinematic craft, they reward engagement. The craft has to be re-engineered to fit the physics of the platform.

#21 — Speed

Film and technology move at 2 different paces. News on X changes daily. Anyone can launch any day and reach everyone. Competitive landscapes are reshaped every week. You have to move fast.

Traditional film moves as fast as it can, but not at startup speed. A director may research a feature film for 2-3 years. Some scripts stay in development hell for a decade. The average time for production of a feature film from concept to screen is 2-5 years. Crews need to be booked 2-3 weeks in advance, sometimes months.

Truly great stories transcend time. They explore deeper, human-centered themes with no expiration date. The films that stick are replayed in theaters forever.

Some anniversaries I watched this year in theaters:

— 50th: One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest

— 50th: Jaws

— 41st: This Is Spinal Tap

— 40th: Back to the Future

— 40th: The Breakfast Club

— 30th: Apollo 13

— 15th: Black Swan

Startups have an expiration date; it’s always around the corner. They’re default dead.

They can’t afford a 3-month production cycle for a brand documentary. So the types of productions that make sense for startups are more limited, and need to stay lean and move 2x as fast.

The medium rewards craft, perfecting every detail in the image (costume, production design, lighting). This is how artists move forward in their careers and get respect from their peers.

Startups don’t have time for that.

#22 — Showing vs Telling

Cinematic storytelling is all about showing, not telling. Technology Twitter rewards long, cerebral rants (like this Substack post) that dive deep into a train of thought through written language. The visual medium rewards you when you deliver images and create watchable results.

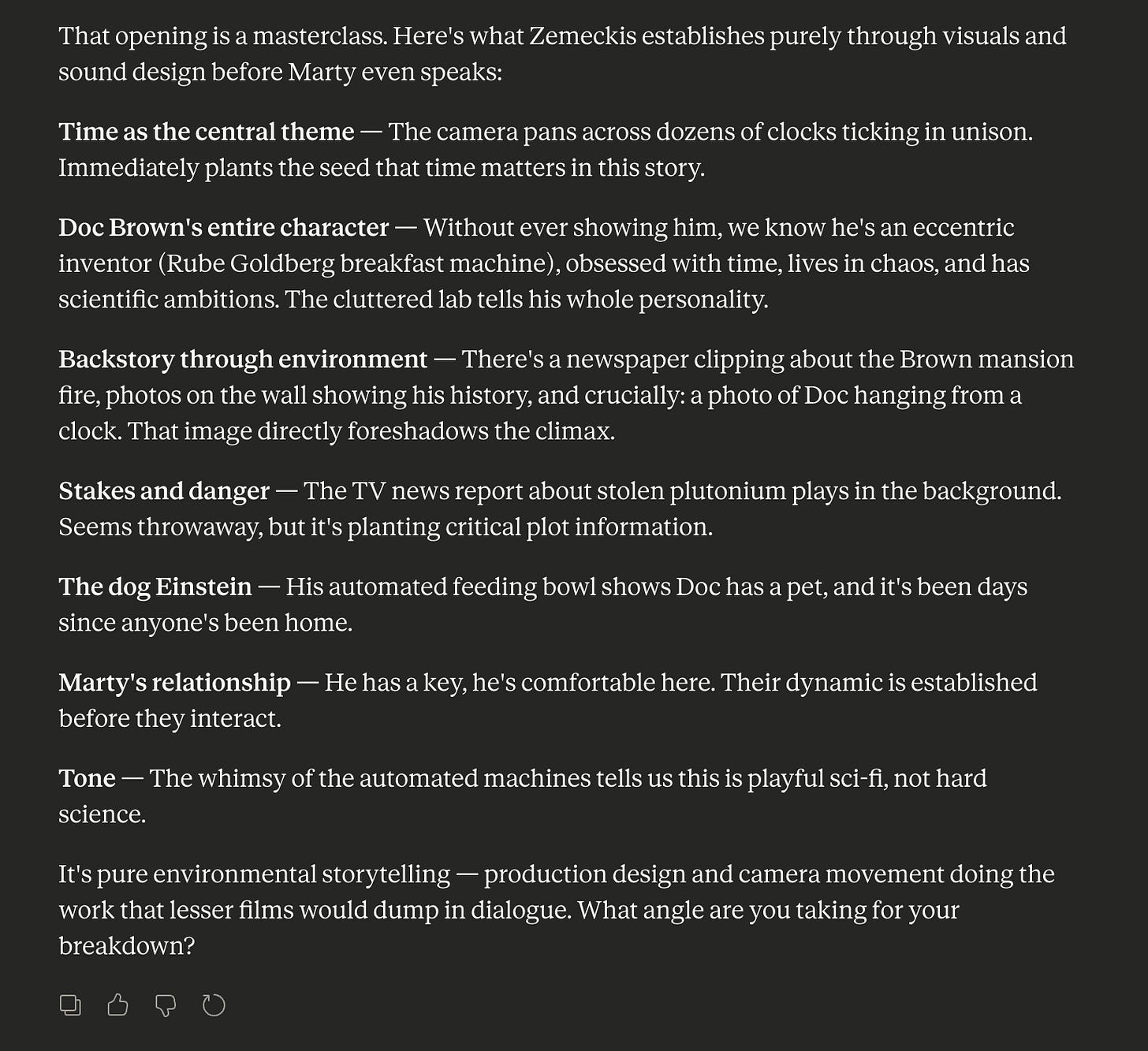

A great example of visual storytelling is the first 2 minutes from Back To The Future. I’ll just let Claude explain:

You get big on Tech Twitter by constantly having something new to say. Pushing for an intellectual edge, knowing what comes next in 6 months. This intellectual mind-dumping actually hurts you in writing for the screen.

#23 — Cinematic Opportunity

Software engineering is not very cinematic. The process does not have many visual elements that you can anchor an effective visual story against. You have:

environment

an office (hopefully it looks good)

individual

wide: someone sitting, typing at a laptop

close-up: hands typing on keyboard

extreme close-up: eyes looking around the screen

medium close-up, over-the-shoulder: typing at a laptop

many more ways to say—typing at a laptop

team

wide: collaborating at a whiteboard

A very limited shot grammar. You can do sitting or standing interviews, have people walk through the space—then you’re out of cinematic options (so you add motion graphics to spice things up..) So your remaining tools are to focus on character arcs, interpersonal conflict, and situation-based drama.

Deeptech has many visual anchors: bio labs, warehouses, robots, rocket engines, satellites, the open ocean, defense testing in the desert. The whole physical world is your oyster. Things explode, fall down, break, make noise, talk.

Opening shots from S3 Episode 41 with Extropic:

Pure software development happens in 1 place, an office. And the product is invisible.

This does not inspire great visual stories, so they do not get produced.

#24 — Physicality

Film work is physical. Going to locations, up and down flights of steps, doing scouts, meeting people, moving heavy gear, setting up lights, tearing everything down, offloading SD cards at home. It is hands-on work, physical work. Only becoming digital later in post-production & distribution.

While I was an engineer, I would be at my laptop 8-10 hours a day, otherwise in meetings or commuting. There is no physical, mobile aspect to software development. Some engineers are very comfortable with that controlled, sedentary aspect to the work. Relaxed, plenty of room to think.

Film production doesn’t offer that luxury. You’re constantly going from writing in solitude to filming on location, and back again. Constant context switching between very offline and very online. In traditional film, production days can be 12hrs+ long.

You can’t write an automation from home for the physical work. It’s structured chaos every time.

Career Engineers Who Became Filmmakers (Few)

To my knowledge, in film history, there hasn’t ever been a mainstream director who came from a sustained career in software (>2-3+ years) and successfully transitioned to film.

There are only 2 prominent cases that come somewhat close.

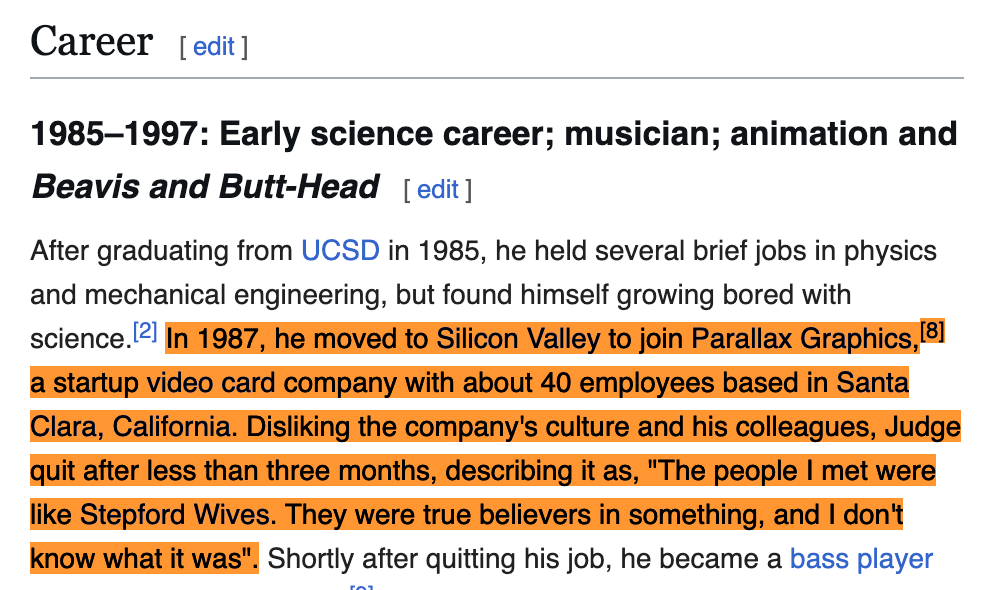

Mike Judge (creator of “Silicon Valley”) worked in tech for 3 months before leaving to become a bass player:

Shane Carruth, a software engineer for 2 years developed flight-simulation software, made 2 films before ultimately exiting the industry:

Otherwise, it’s never happened.

Just a Few Engineers

In September, I was talking to Donald Jewkes at Cursor’s studio in North Beach. The room was quiet, tables overturned, lights off. Sunlight from the windows poured in, bouncing off the floor.

I explained my apprehensions about leaving engineering for film. I was already 8 months in, the decision was effectively made. But I was struggling—for all the reasons I’ve just listed.

Ben: “I’m worried if I keep at this career, I won’t earn as much as I would in engineering.”

Donald: “I mean…you can make the same amount doing film.”

Ben: “…but there aren’t really any software engineers who are filmmakers here. I think it’s just us.”

Donald: “…”

Donald: “Yeah, I think it might just be us.”

Those here—those who came here as career engineers—are up against incredible odds to become storytellers.

An entire industry must form. Podcasts are not enough. Corporate video is not enough. 1m10s clips are not enough. 2 film studios are not enough.

We need a talent pool of professional actors, writers, directors, cinematographers, producers. All tech-aware. Living here. Many productions running. Forward career mobility.

Silicon Valley must begin to produce great storytellers.

I think you're amazing for documenting this. I've watched your videos over the years in preparation for Big Tech interviews, and I think you have a really great way of communicating with feeling and emotion. To me, it felt more human compared to watching a lot of other tech interview prep videos on YouTube where people explained things in a dry, monotone manner. All the best and excited for what's ahead!

This is awesome, and these lessons really resonate for me as a former product manager turned writer/director. Excited for your journey! If you’re interested, would love to connect and trade stories of my transition into filmmaking (just wrapped on my first short)